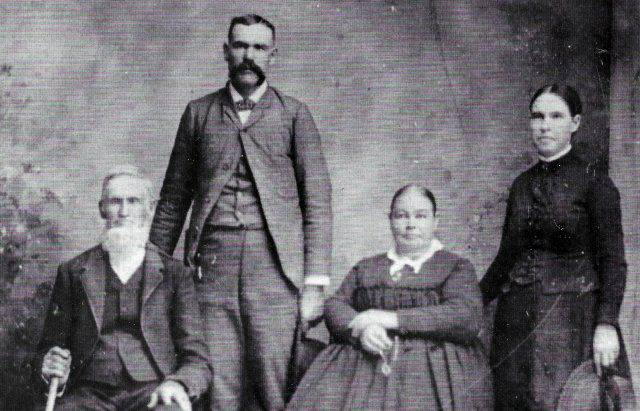

Edwin Whiting, Lorenzo Whiting,son, Hannah Haines Brown Whiting, Abby Ann Whiting Bird

“Emigrants for Utah, Company which left Florence, Iowa, June 5th. Elder Philemon C. Merrill, Captain”

Emigrants of interest are Elisha Edwards (Edwin’s Missionary Companion), Hannah H. Brown, Edwin Whiting.

Source 6 Aug 1856, pg 8 Deseret News Online

********

A Second reference to this company is noted in the Mormon Overland Trail Records

Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel, 1847–1868

|

||||

Brown, Hannah H. ( Age Unknown)

Edwards, Elisha (49)

Whiting, Edwin (46

On the fifth of July 1849, the Nauvoo widow Abby Cadwallader Brown would take pen in hand to consent to the marriage of her fourteen-year old daughter, Hannah. A thirty-six-year-old brickmaker from New York State, by the name of Horace Bristol, had secured permission to make the young Quaker girl his wife. (1)

Perhaps the untimely death of Hannah’s father contributed to the decision that she should marry a man more than twice her age. Dr. Abia William Brown had died of typhoid fever in August of ’48. The Brown family had been poor though not utterly destitute; Abia’s unexpected demise now plunged his dependent survivors into dire straits. Considering the family’s situation, we might surmise that Hannah’s mother was ready or even eager to welcome sons-in-law who could assume part of her financial burden. Of course, early marriages were not uncommon in this era. Abby’s first son-in-law, William Derby Johnson, had married sixteen-year-old Jane Brown only three months after Abia’s death. Now it was Hannah’s turn.

Abby met the requirements of the law with the words “This is to certify that I give my Concent for hannah Brown My daghter to mare Horace Bristol for his wife.” (2) If Abby’s spelling was a bit wanting, she was still more accurate than the county officials who accidentally transcribed the bride’s name as “Sarah” on the accompanying marriage certificate. Two days later, on July 7, a William Haney performed the marriage ceremony; the event was officially entered in the county register on August 6, again with the mistaken name “Sarah”. (3) Fourteen days later, Hannah marked her fifteenth birthday.

The family of Dr. Abia William Brown had lived in Nauvoo only about eighteen months, having arrived sometime just before the winter of 1847–48. (4) At the time of Hannah’s marriage to Horace Bristol, none of the Browns had yet become a Latter-day Saint, though they were favorably impressed by the empty cocoon called Nauvoo, now vacated and its former occupant flown westward. As the Saints made their abrupt departure into Iowa, abandoned properties were put up for sale at wonderfully deflated prices. Dr. Abia Brown was one of the Nauvoo newcomers who found an enviable deal in real estate because of the Mormons’ expulsion.

A grandson later wrote:

“Arriving in Nauvoo, he met President Brigham Young, who as soon as he saw grandfather’s horse wanted to buy it and made a good bargain in different kinds of household goods. . . . Among the things he bought from Brigham Young was a stove. This was the first cook stove my grandmother ever had.” (5)

A number of descendants have related how Abia was very sympathetic toward the persecuted people called Mormons whom he encountered in the Nauvoo area:

“He learned to respect and love the Saints who were living there and refused several times when men would try to get him to help make the Saints hurry up and leave. . . . He would always say they were a good quiet people and good citizens and why get rid of them. . . . One man said to him, “I believe you are one of those damn Mormons too.’” (6)

Abia was able to purchase land from the Mormon agent, and he and his family spent the winter in a cabin while they waited for the family who owned the farm, house, and orchard to move out.

In a letter to an acquaintance, he wrote: “From the old cabin where we have spent the winter, and for the most part a pleasant one… I write this… The city and country are filling up very fast since the Mormons left, although there sill remains a large amount of property in the hands of the agent. It is astonishing what a vast improvement they have made in a few years amid all the hostility that was shown them. To me it appears singular that a people having so much industry and attending to their own business, could find time to commit all the devilment laid to their charge. (7)

Just as important as finding cheap property, Abia had found what he considered to be a beautiful city, a promising location for permanent settlement after many years of nomadic wandering. Practicing medicine had kept him on the move seeking clients. In spite of this world’s disease and suffering, physicians of the early nineteenth-century American frontier were hard-pressed to make a decent living. He later wrote to his mother detailing the family’s efforts to survive, and included this charming excerpt about Hannah:

“… Hannah is going to be the flower of our flock in every way. She excells her sisters in industry, being faster, and if she keeps on, will soon excell in personal apperence…(8)

Unfortunately, Abia was never to know whether his own words were prophetic or not. Soon after, he fell victim to typhoid. At the time of Abia’s death (five months after the composition of the 1848 letter), his surviving children had reached the following ages: Ann Kempton, 17; Jane Cadwallader, 16; Hannah Haines, 14; Mary Trotter, 10; Abia William Jr. (Will), 8. One month after the loss of her father, ten-year-old Mary would also die, most likely from the same epidemic.

The Browns’ high hopes for a bright future in Nauvoo had been dashed. That they were already struggling financially is obvious from letters which included Abia’s pleas for continued charity from his merchant relatives in Philadelphia. “The family was forced to give up the idea of buying the farm.” (9)

By the end of 1848, Hannah’s sister Jane, described as a “quaint sweet little Quaker girl, very small, black hair and eyes,” had married a Mormon and left home. All of this brings us back to where we started: The context for Hannah’s marriage contract was less than ideal; the alliance to Horace Bristol may have been (at least partially) a result of family financial pressures. When the 1850 federal census of Hancock County, Illinois, was taken, Hannah, her mother Abby, her older sister Ann, and her little brother Will were all tallied as members of Horace Bristol’s household. Essentially, they were deemed his dependents.

In 1851, at the age of sixteen, Hannah gave birth to a son who would live but one week. (10) Four months after her baby Mifflin’s death, young Hannah left her husband, by which time her mother and siblings were surely also out from under Bristol’s roof.

We can only imagine the tragedy of Hannah’s position: she was herself but a child, yet she had already witnessed the burials of a father, a ten-year old sister, and her own child. Now she was a single woman, having fled from her marriage in an era when doing so almost inevitably brought great shame and a sullied reputation. In these difficult days, Hannah would have benefited tremendously from the faith of her father, Abia, who had asserted in an earlier letter that “Providence often opens a way when there apperes to be no way,” and that he would “trust to Providence who has never yet forsaken us.”

Above: Mapleton, Utah Home of Hannah H. Brown and Edwin Whiting

Hannah next appears to have surfaced in Kanesville (later to be known as Council Bluffs), Iowa, where her older sister Jane had been living since shortly after 1848 with her husband, William Derby Johnson. (Their daughter Julia Ann was the wife of Almon Babbitt, after whom Almira Mecham Palmer in 1841 had named a son–later to become one of Edwin Whiting’s stepsons).

Living near (or possibly with) her sister in Kanesville, Hannah would learn more about Mormonism, since Jane, as the first of her family to do so, had in 1850 exchanged the Quakerism of her parents for the Mormonism of her husband. This would have a great impact on the course of the entire Brown family’s future. Abby Cadwallader Brown became a Mormon in 1853. Hannah seems not to have rushed into the waters of baptism, but waited until 1854. Abia Jr. (Will) was baptized much later, after moving to Utah.

The family eventually migrated to Utah in a piecemeal fashion, Hannah quite independently.

We know very little concerning Hannah’s activities while living at the Missouri River between 1851 and 1856. If she associated closely with her sister Jane Johnson, Hannah may have followed the Johnsons in 1852 when the family moved for a short season to Traders Point, six miles from Kanesville.

Meanwhile, in Illinois, Horace Bristol decided to pursue a divorce. The reasons for Hannah’s separation from Horace are unknown, but the grounds on which he sought a divorce are documented. Their case came before the Adams County circuit court in early 1855. Only a few court documents pertaining to their case have been preserved. (11) They provide the briefest glimpse of the matter–almost nothing that can be considered conclusive or that might reveal motives. While filing his petition, Horace as complainant attested that he had resided in Quincy, Adams County, Illinois, for ten years. Furthermore he claimed “that on or about the first day of May a.d. 1848 he was lawfully married to Hannah H. Bristol at Nauvoo Hancock County Illinois that without any cause or provocation on the part of [himself] the said Hannah left [him] without his consent, and departed from said State of Illinois to Council Bluff City … on or about the first day of August a.d. 1851.

Horace continues his complaint with the charge that Hannah had remained in Council Bluffs ever since her departure from Illinois and could be found residing there “in an open state of adultery.” Because Hannah never appeared in court to respond to the charge against her, the court ruled in favor of Horace Bristol and granted the divorce he sought. It seems Hannah never received her summons to appear in court. The Adams County sheriff certified that he could not locate her and therefore could not serve a summons. Notification of the summons was published for six weeks in the Quincy Herald (from January 8 until February 12, 1855).

As for the credibility of Horace’s charge against Hannah, one might note that his memory was deficient enough for him to miscalculate the date of his wedding anniversary by a considerable length of time: in his petition, he got not only the day and month wrong, but the year as well.

After the divorce, Horace disappears completely from Hannah’s history. Family records give Hannah’s baptismal date as August 15, 1854. Elder Benjamin Clapp baptized her and Elder Lyman A. Littlefield confirmed her. (12) Since this significant event occurred a considerable time before the divorce, and since Mormon converts were all expected to gather in the West at first convenience, it seems that the legal aspects of her separation were of little concern to her. Essentially, she would be leaving the practical jurisdiction of the United States to start life anew.

Hannah earned her living and her “fare” for crossing the plains by cooking and washing for two motherless children, the boys of a certain Francis Brown. She “drove an ox team” herself as a member of the 1856 Philemon C. Merrill Company. Edwin Whiting, returning from his mission to Ohio, had also attached himself to this pioneer company and thereby met Hannah. We know nothing about their meeting–only, as one descendant tersely remarked, that Edwin eventually “decided she would make him another good wife. ” (15)

Above: Hannah Haines Brown Whiting

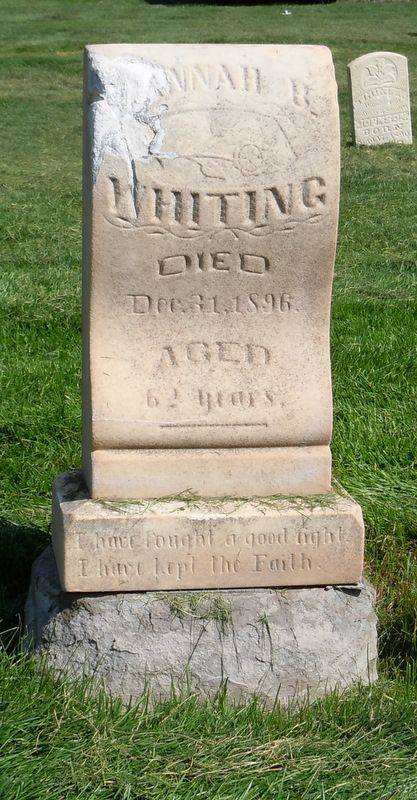

As noted earlier, Edwin and Hannah were married by Brigham Young in his Salt Lake City office on October 8, 1856. The events of Hannah’s life as Edwin Whiting’s fourth wife in plural marriage have been recounted in earlier chapters, so we now turn to the twilight of her life. During the six years of her widowhood (1890–96), Hannah lived in Mapleton near her two living children, Abby Ann and Lorenzo. By her later years she had grown quite heavy. Her general health could not have been good, but the sickness that led to her death came on quite abruptly: she died of blood poisoning. As one account noted:

“She died on the 31st of Dec. [and] was buryed on New Years Day. Her death is suposed to be caused by blood poison, originating in a felon on her finger. Her deat[h] was very unexpe[cte}d being confined to her bead but a few days. She had always prayed that she might not live to be helpless and become a burden on anyone, and God truely answered her prayers.” (14)

Cemetery Headstone for Hannah H. Brown Whiting – Evergreen Cemetery, Springville, Utah

In 1896, at year’s end, Oliver Huntington made the following entry in his diary: “December 30, 1896, about one o’clock at night the Bishop of Mapleton came for my wife to go up there to old Sister Hannah Whiting’s as she was probably dying and her only daughter wanted Aunt Hannah Huntington to be there and do the last services for our old neighbor and friend. She died about 30 minutes after my wife got there.”

Huntington again mentions Hannah Whiting on New Year’s Day: “January 1st, 1897, Hannah [his own wife] and I clothing in a Temple suit.” (15) Whiting descendants today would eagerly read Huntington’s ‘biographical sketch’ prepared for the funeral-if only his notes still existed.

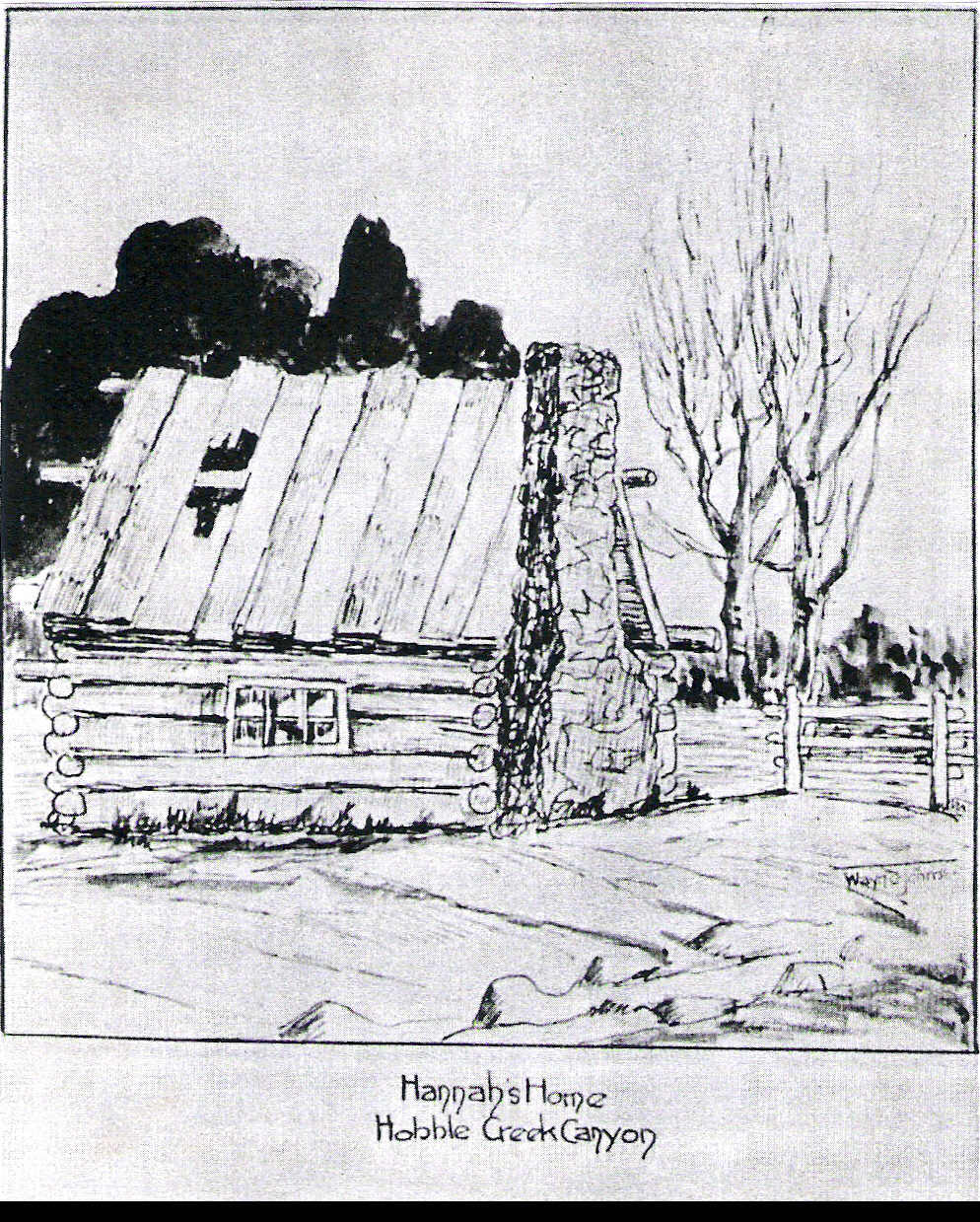

Edwin and Hannah H. Brown Mapleton, Utah Home

Nine years after Hannah’s death, her Mapleton home, built by son-in-law Charles Bird, was purchased by Horace Perry. In 1914, he added a kitchen, bedroom and porch to the structure. A large Lindon tree, still standing on the property (1995), was undoubtedly planted by Edwin, who also planted four pine trees on the site. Horace Perry’s daughter, Leah Perry Wilson, recalled that Edwin and Hannah left” an apricot and pear and an Emmy Wansett’ apple tree.” Emmy Wansett was an Indian squaw familiar to the Mapleton locals. Warren Perry remarked that one particular apple tree on the property, perhaps the so-called “Emmy Wansett’ tree.” Emmy Wansett was an Indian squaw familiar to the Mapleton locals. Warren Perry remarked that the so-called “Emmy Wansett” tree had four different kinds of apples growing on it-a trick achieved by grafting.

Edwin and Hannah and their Children

“Hardships and trials of early pioneering softened her life, giving her a lovely disposition.” Wrote granddaughter and namesake, Hannah Bird Mendenhall. “She was ever charitable, tolerant, thoughtful of others, sacrificing and joygiving… . She made this statement that all the other wives of Grandfather were to her as sisters and she loved and respected them in their homes as such.” (16)

Hannah Mendenhall’s sister Jennie Hill recalled, “Hannah Whiting was a hard working woman, neat and clean and thrifty. I have often said she was the best cook I ever knew for having so little to cook with. She made good pies. My sister Emogene and I found one on her pantry shelf. We did not ask but ate a good-sized piece. She soon missed her pie and mother was informed. Oh boy! Grandma did not mind us eating the pie but to do so without asking was unforgivable. So we were told to go back to her house and ask her forgiveness. And-bless her heart -when she saw how we cried, she took us in her arms and cried too. It was a good lesson in honesty. ” (17) Such are the tributes and anecdotes we share after a relative is gone; seldom if ever can these scanty words do complete justice to a long life well lived.

Sketch of Hannah’s Hobble Creek Canyon Home by Grandson Wayne Johnson

Notes

Horace’s profession is given in the 1850 federal census of Hancock County, Illinois.

Hancock County, Illinois, marriage certificates 1844-1850, license no. 1445, fhl, film 1,532,146.

Hancock County, Illinois, register of marriages 1829-1857, fhl, film 954,177.

Macy B. Robinson, “Sketch.” Robinson indicates that Abia moved his family to Nauvoo at this same time (about 1845), but Abia’s 1848 letter shows their final move to have come considerably later.

Macy B. Robinson, “Sketch.

Abia William Brown Sr. to Samuel E. Stokes, March 1848 (typescript), hdc, ms 747.

Abia William Brown Sr. to Ann Kempton Brown Haines, December 28, 1843 (photocopy) hdc, ms 747.

Dezzie D. Brown Lamb, “Biography.”

Our knowledge of this child comes not from local records of the Midwestern states of Ohio, Illinois, or Iowa, but from the St. George Temple Records. These temple records may be the only extant documentation that there ever was a Mifflin Bristol. In 1879, Hannah and Edwin performed a vicarious sealing ordinance for little Mifflin, adopting him into the Whiting family. Hannah on that occasion informed the temple recorder that her child Mifflin was born April 3, 1851, in Clark County, Iowa, dying just days later, on April 10, in Goshen, Columbiana, Ohio. A comparison of these dates with the dates of Hannah’s marriage to and divorce from Horace Bristol reveals that Mifflin was not an illegitimate child, as some Whitings in recent years have erroneously conjectured.

Abia’s 1843 letter to his mother, Ann Haines.

Circuit Court of Adams County, Illinois, divorce cases 1825-1922, Box C-26 Case 641, fhl, film 1,845,492.

Jennie Bird Hill, “Hannah.”

Jennie Bird Hill, “Hannah.”

Joy Wells Dunyon, first missionary diary, hdc, ms 9425, pp. 135-36.

Oliver Huntington, journal.

Hannah Bird Mendenhall, tribute.

Jennie Bird Hill, “Hannah.”

Note: This biography comes from the Book, Edwin Whiting and His Family, Written 1999, by Marie J. Whiting and Marcus L. Smith. Other photos supplement this account.

Hannah Haines Brown was born in Clumbiana, Ohio, June 21, 1834, daughter of Abia Brown and Abbie Caldwalder. Hardships and trials of early pioneering softened her life, giving her a lovely disposition. She was ever charitable, tolerant, thoughtful of others, sacrificing and joygiving. As a child of fourteen, at the time of Grandmothers death, I cannot recall ever hearing her speak an angry word. Quoting from a letter written in 1843 by her father to his mother, Ann Haines Brown, which I have in my possession, and nearly one hundred years old, he says: My dear little girls are a great help to their mother and me. Jane is taller than Ann, but Ann is quite womanly and trusty, but Hannah is the flower of the flock in every way. She excells her sisters in industry, and if she keeps on will excell in personal appearance. All through her Grandmothers life, she had these chacteristics which make her a sweet and lovable woman. She made this statement that all the other wives of Grandfather were to her as sisters and she loved and respected them in their homes as such.

By Hannah Bird Mendenhall