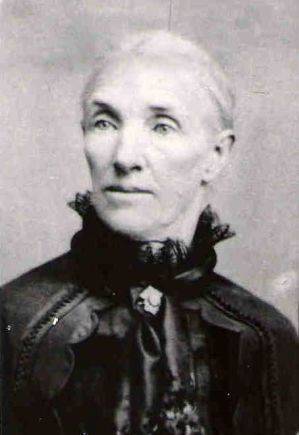

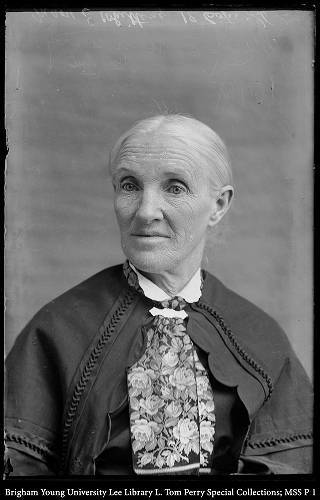

Mary Ann Washburn Noble Whiting Biography

Biography of Mary Ann Washburn Noble Whiting

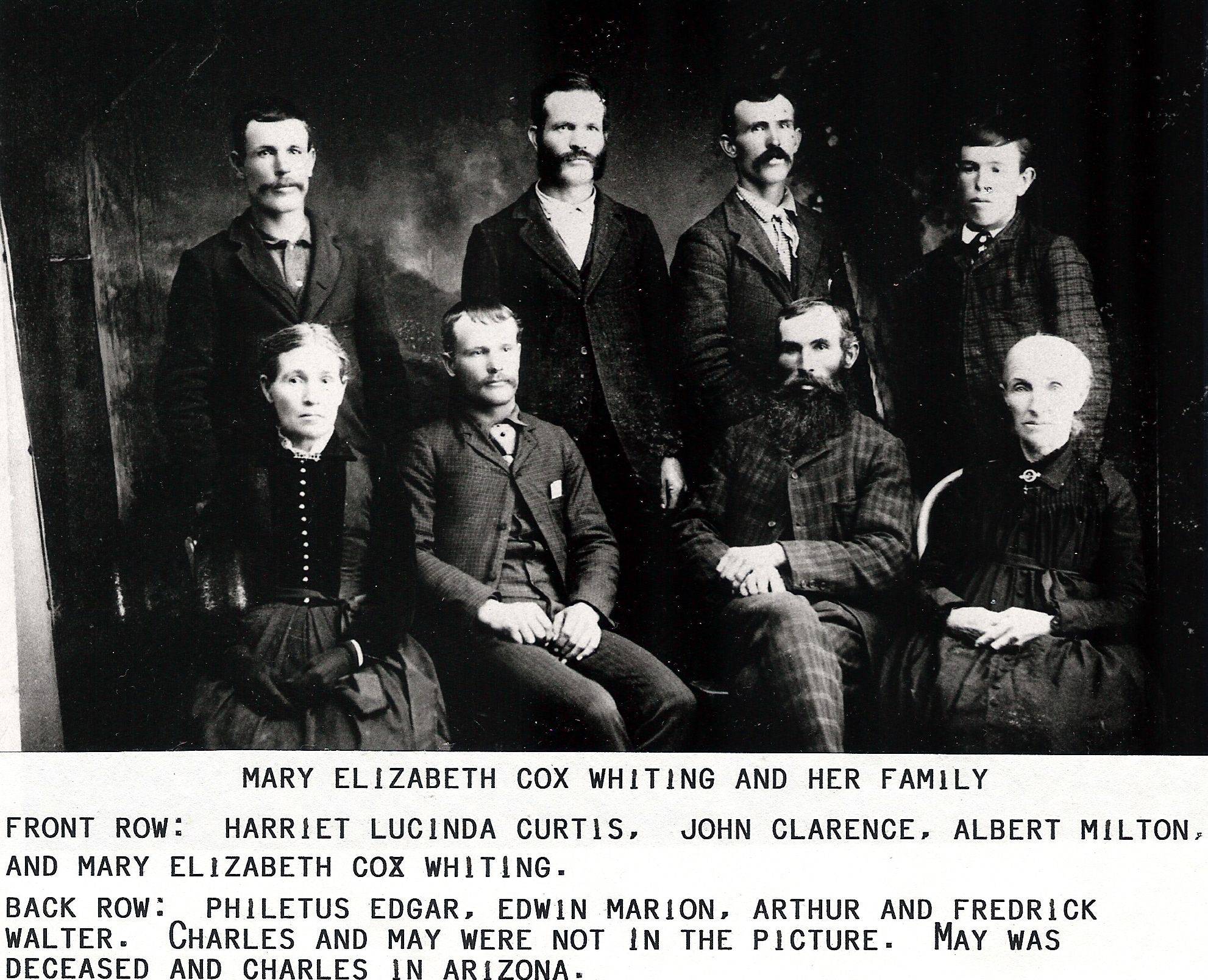

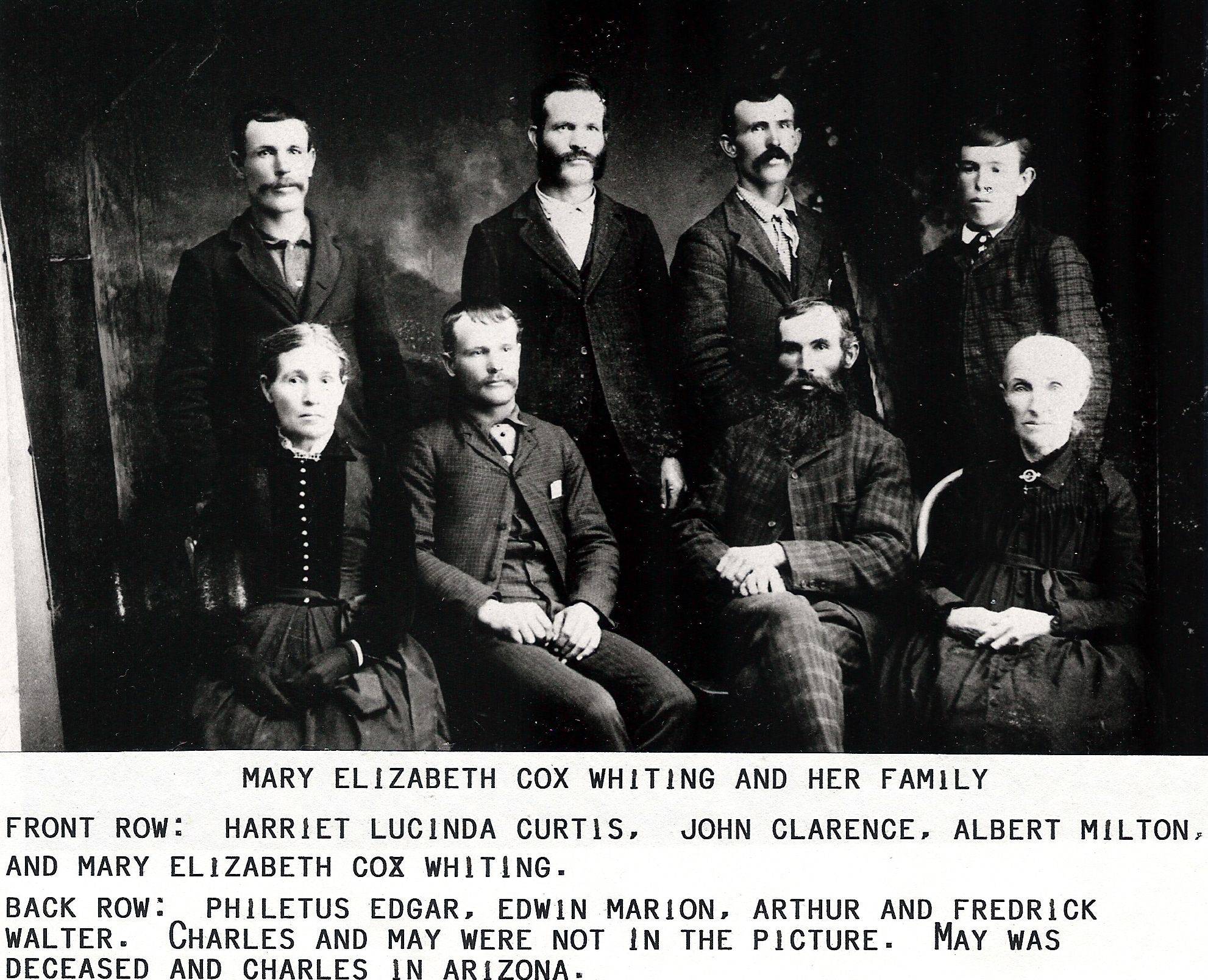

Of Edwin Whiting’s five wives, Mary Ann was his last in order of marriage and the only one to precede him in death. Even so, their marriage in plurality extended over a period of twenty-five years. Mary Ann’s is a sad story in many respects, although few details have survived to the present day. What we do know about this sorrowing woman comes to us in large part from oral tradition, circumstantial evidence, and from the writings of four Washburn descendants, Geneva D. Larson, Lorena E. W Larson, Susannah Washburn Bowles, and Mary Ruperta Whiting Smith. All this combined forms the basis for the biographical sketch presented here.

On [15 November 1828 or 18 Nov 1827] in [Sing Sing or Mount Pleasant], Westchester County, New York, Mary Ann was born to Abraham and Tamer (Washburn) Washburn as their second child. An older brother, Daniel, had been born in 1826, and an adopted son, William Davis, may have already joined the family too by this time. Eight additional brothers and sisters would join Mary Ann under her parents’ roof in subsequent years, but only five of these siblings would survive childhood. Tamer had borne the surname Washburn before her marriage to Abraham. Her father, Jesse, had been Abraham’s great uncle. With Washburns on both sides, Mary Ann’s ancestry is replete with other preeminent surnames of colonial New York and New England: Cornell, Fowler, Hawxhurst, Underhill, Winthrop, and Wright, to name a few. Yet in spite of being offspring of some leading or well-established families, Abraham and Tamer were nevertheless commoners fruit that had fallen far from the trunk of the old colonial elite. Abraham was a tanner and shoemaker and his father had been a farmer.

The ardently religious environment of Mary Ann’s childhood home must have left its mark upon her. Quakerism was the Washburns’ original lodestar. Mary Ann’s father and two uncles had been named Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob after the ancient Hebrew patriarchs. Jacob was probably the first of his family to turn from Quakerism, though not away from religion, for he became a Methodist minister. Abraham was a strong advocate of abstinence from liquor and tobacco. As for Tamer, her strictness in the practice of religion was to become the stuff of family legend. She was staunch in her application of the Quaker code of conduct: the Sabbath was inviolable; prayer and worship were mandatory; in matters of attire, extravagance was to be shunned.

For all the rigor of their Quaker ways, the Washburns were human enough to enjoy themselves: “The Quaker Sabbath commenced on Saturday at sundown and closed Sunday at sundown. No member of that faith was supposed to laugh during that period, but as the Washburns said, Quakers were very human, and at the close of the Sabbath the young people had a very good time.”

Abraham Washburn had been a tanner and cobbler from his early days in New York. At one time, he owned a tanning and shoemaking establishment, where he instructed others in his craft. We can only wonder how many pioneer feet fled Nauvoo or crossed the plains in shoes of his making. He continued in this occupation after coming to Utah; it was said that Abraham Washburn kept the residents of Manti well shod.

In about 1836 or 1837, Orson Pratt was making his way through the lower Hudson River Valley, on a proselytizing tour. During his travels he preached the strange new American religion called Mormonism to the Washburn family. By the time Pratt arrived in Sing Sing (now Ossining), Abraham (like his brother Jacob) had already been through one conversion, exchanging Quakerism for Methodism and persuading his family to follow suit. Tamer, now faced with yet another potential change, reacted to the new itinerant preacher with righteous indignation.

Determined that Mormonism was a dangerous deception, “she turned on Brother Pratt and poured out the venom of her wrath in no gentle tones. Her husband tried in vain to soothe her.” Orsons Pratt’s famous brother, Parley P. Pratt, baptized Abraham on 6 Feb 1838, in spite of Tamer’s strong initial opposition. Her conversion is said to have come soon after an evening meeting conducted by Orson Pratt and attended by Abraham, during which a message came saying that Tamer had fainted, or, as in one account, that she was “in a terrible nervous condition on account of his being at a Mormon meeting.” As Abraham made ready to leave to attend to his troubled wife Brother Pratt said, “Be of good cheer, Brother Washburn, for in a very short time your wife will be a member of the Church.” (1)

It was but a few weeks later that she asked Brother Pratt to baptize her. Tamer’s subsequent loyalty to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was unwavering. Animosity toward the Pratts disappeared. Both Parley and Orson Pratt stayed as guests in the Washburn home while preaching in New York, and two of Abraham Washburn’s sons would later be named after the renowned Pratt missionaries. (2) Family tradition maintains that the Prophet Joseph Smith himself, during an evening social at the Washburn home, pronounced a blessing upon Tamer’s head, assuring her of salvation in the celestial kingdom because of her liberality. One might naturally conclude that Tamer had become a Mormon through and through. But family members recalled how she held to many of her Quaker ways and attitudes for many years after becoming a Latter-day Saint. On one of his visits to the Washburns, Orson Pratt brought his wife along. She was wearing a lace cap ornamented with ribbon and small artificial flowers. “Sister Washburn had not yet sufficiently recovered from her Quaker notions to be able to tolerate these excessive practices, so she asked Sister Pratt to please remove the trimmings from her cap while she remained her guest. To please Sister Washburn, Sister Pratt complied with the request. In years after, Tamer laughed as she related the story, because she herself wore just such little lace caps to the end of her days and enjoyed having them handsomely decorated. “

Just how charitable Tamer was (and how supportive she became of the Pratts and Mormonism) is illustrated by the following anecdote: “Abraham was a prosperous businessman and he gave Tamer a regular allowance of seventy-five dollars a month. She deposited a part of her allowance each month in the bank. Once Orson Pratt was going to England on a mission. He arrived in New York with no money to pay his traveling expenses. Tamer gave him enough money from her savings account to pay his passage to England.” Such a gift would have been a considerable sum. But this year (1837) brought Mary Ann’s family not only a new gospel; it brought tragedy as well. Mary Ann’s older brother Daniel and their little sister Elizabeth Underhill died. Mary Ann was eight or nine years old at the time, Daniel ten, and Elizabeth three. Tamer had had a dream forewarning her of impending loss. In this dream Tamer “went to heaven. Everything was beautiful and in perfect order. She visited many wonderful places. In beautiful parks she saw many groups of happy children at play. They were in the charge of and their play was supervised by very fine, intelligent women. She came to one group where two of her own children were playing. She was surprised to see them there, and when she looked up inquiringly into the face of the lady who had them in her charge, the lady said, ‘Sister Washburn, it is your privilege to see before- hand where your children will be so that the parting will not be so hard.’ In a few weeks, the two children died. Sister Washburn said that when they died, she could not shed a tear because the vision was continually before her mind.”

Tamer would lose another three children after moving to Nauvoo, all infants. Mary Ann, as a mother herself in later years, would lose four of her own children; we might wonder if some kind of comfort came to Mary Ann as it did to her mother Tamer in Sing Sing, or if Mary Ann bore her sorrow in some other way.

As reported by Geneva D. Larsen, a great grand-daughter, Mary Ann drew strength during her own bereavement by reflecting on the dream Tamer had related to her. The Washburns remained in Sing Sing, with Abraham acting as president of a tiny LDS branch there, until the spring of 1841. (During this time Abraham was ordained a teacher and then an elder by the Pratt brothers.) Abraham then sold his tanning and shoe business to one of his wife’s relatives and moved his family to Nauvoo, Mary Ann being about twelve or thirteen years of age. (3)

At the time of this move, the living children of the Washburn family were Mary Ann, Emma Jane, always called Amy (age 11); Daniel Abraham; and Sarah Elizabeth (age 2). Leaving New York state for Illinois, Mary Ann with her siblings left behind the only grandparent they might have known: Susannah Tompkins Washburn. Since Susannah apparently lived until 1861, long after Abraham and Tamer had established themselves in Utah, we might well wonder what correspondence, if any, was exchanged in later years between the aged Susanna and her Mormon daughter Tamer.

Certainly Susannah received word when her namesake, little Susannah, was born to Abraham and Tamer in 1843 in Nauvoo. Living with the body of the Saints in Nauvoo, Abraham was ordained a seventy by Hyrum Smith, the patriarch of the Church and brother of the Prophet. Abraham also attended the Nauvoo School of the Prophets and served as a member of the Nauvoo Legion. He established a tanning and shoemaking business, advertising in the Nauvoo Neighbor under the name “Abraham Washburn & Company.” His business was located on Warsaw Street (now Rich Street), just north of Parley Street, on the east side of the road. Here with the main body of Latter-day Saints, the young Mary Ann Washburn was able to observe the Church and familiarize herself with its doctrines during some of its formative years. The Prophet Joseph Smith was often a visitor in the Washburn home and was involved with Abraham in land transactions. Abraham assisted in public works and in the finishing of the Nauvoo temple. And on the famous occasion of Joseph Smith’s farewell address to the Nauvoo Legion, Abraham stood at the corner of the platform from which the Prophet delivered his stirring address. Two years later Mary Ann’s father and, no doubt, his wife and four children as well were in attendance on the occasion when the “mantle of the Prophet fell upon Brigham Young.” In his later years, Abraham took pleasure in rehearsing these events to his family and friends. It should be clear that Mary Ann had been inducted into Mormon ways early in life. Her parents had received missionaries when she was eight or nine. Two of the faith’s most charismatic missionaries had frequented her childhood home. In her early teens she had witnessed the comings and goings of the illustrious prophet-founder of Mormonism himself. Over the course of two years, she watched the Nauvoo Temple gradually rise from moonstones near its foundation to sunstones at the top of the pilasters.

Now at age fifteen, long before the completion of the temple’s final story and octagonal tower, she would hear rumor and then confirmation of the Prophet’s brutal murder and would witness all of Nauvoo beset with grief; at age seventeen or eighteen, she would receive her endowment in the completed temple during the flurry of temple activity just prior to the exodus. (Her parents were endowed that same day, 6 January 1846.) Like the Whitings, the Washburns did not escape the persecutions and harassment that befell the Saints during these difficult months of the winter of 1845- 46.

Mary Ann was a witness to both Nauvoo’s brightest and darkest days. On one occasion a mob leader started up the stairs of the Washburn home. Tamer “caught him by the coattail and pulled him down again. He later returned with the mob and took possession of their home and all of their belongings, turning the family into the street.” In the months before the Latter-day Saints left Nauvoo, Abraham Washburn found his funds nearly exhausted. “He needed money to fit himself out for the journey across the plains. Knowing that his brothers had ample to send, he decided to write them. He wrote a history of the mobbings and persecutions, the hardships and the trials [his family] had gone through … and added that he was tired of it. In a short time, money enough to fit him out well with team, wagon, and provisions for the journey came to him.”

Challenged by their reduced financial circumstances, Mary Ann’s parents learned to subsist as they would have to again during the early settling of Manti, Utah. “Tamer often laughingly related the following incident which happened some time before the Saints were compelled to leave … Nauvoo. She said Abraham was so devout and always asked the blessing on the food, no matter how scarce it happened to be. One morning, when their money was nearly gone, she fried hot cakes for the family breakfast. There was very little to go with them to make the morning meal. She was thoroughly disgusted with such conditions, but after morning prayer, Abraham sat at the table and thanked the Lord for the food and asked Him to bless it, just as he had done when they had plenty. She, at that moment, could see nothing to be thankful for, and when Abraham said amen, she said, ‘Oh damn the stuff.”

Tamer, every bit human, was no stranger to frustration. And who can’t sympathize with her ability to look back on even a few of the hardest times with a degree of bemusement? It seems improbable (though not impossible) that Mary Ann could have entered into plural marriage with Bishop Joseph Bates Noble of Nauvoo at the age of fifteen – on 8 September 1843 (as reported by J. Ordean Washburn). Yet Abraham and Tamer Washburn were well enough acquainted with Bishop Noble by 1845 to name one of their children after him, which indicates some close bond or attitude of respect.

We know that Mary Ann was sealed to Bishop Noble (who was eighteen years her senior) in the Nauvoo Temple, 6 Jan 1846. She is generally considered to have been his third wife in plurality. Abraham and Tamer Washburn were among the first to arrive in Winter Quarters, Nebraska, during the 1846 winter-to-spring Mormon exodus from Illinois. They were busy establishing their own household and helping establish the temporary colony there on the west bank of the Missouri River, across from Council Bluffs, when Abraham was called to serve as Bishop Noble’s first counselor. Five weeks before giving birth to her own first child, Mary Ann (with her mother Tamer) assisted at the birth of Clarinda Huetta Johnson. This baby’s young mother, Flora Clarinda Cleason Johnson, was feeling abandoned by her husband. She would never see him during the trek across the plains, would divorce him, and then later become Abraham’s wife in plural marriage, Tamer’s sister-wife. In some ways Flora’s situation mirrored Mary Ann Washburn’s: both were significantly younger than their husbands, both were experiencing childbirth for the first time, and both felt dissatisfaction in their marital arrangements. What conversations certainly transpired between them are a matter of speculation only. We rely on imagination alone in any attempt to appreciate or sympathize with their situation: they were young refugees from persecution, essentially single mothers, caught in complex and still somewhat secretive marital alliances, subsisting as best they could in disease-ridden hovels on the edge of the American frontier. Mary Ann’s first child, Mary Elizabeth Noble, was born 25 February 1847. Mary Ann was about twenty years old. Just a week later, Bishop Noble took his fourth wife in plural marriage, the widow Susah Hammond Ashby. (Noble’s second wife, Sarah Alley, had died on the first day of the year.) Unfortunately we have no evidence in contemporary documents to verify the exact date of Mary Ann’s marriage to Noble. This lack of reliable evidence is due to the secrecy veiling polygamous alliances during the first years of its practice among the Latter-day Saints. If a marriage ceremony preceded their sealing in the temple, this would of course have been performed under a cloak of secrecy, since the practice of plural marriage was not officially acknowledged by the Church until 1852/53. Admittedly, in Winter Quarters polygamy (plural marriage) had become an “open secret.” But even then, women living under “the principle” were not addressed by the surnames of their husbands. Mary Ann most likely remained “Sister Washburn” until after her arrival in the Salt Lake Valley.

Only a safe distance of a few thousand miles from Eastern critics would allow her to be called “Sister Noble” in public. Furthermore, in Winter Quarters, Mormon polygamists were not yet in the practice of arranging themselves with a husband and several wives living in a single household. One source tells us that the wives of Joseph Bates Noble were never found living in a single household, not even in Utah.

What living arrangements were made for her is unknown, but it is likely that she was housed with her parents. The Washburns remained for a year in the Great Salt Lake Valley. In December 1848, Abraham was listed among others who participated in a small, competitive expedition to exterminate predatory animals. On 11 Feb 1849, he was sealed by Brigham Young to a second wife in plurality, Flora Clarinda (Gleason) Johnson. (She had been divorced from B. F. Johnson, by whom she had a daughter. The ceremony took place at 3:10 p.m. at the home of Joseph Bates Noble. This seems to indicate that the Wash burns and Bishop Noble were still on good terms with one another. Flora had been the Church’s second Relief Society President, Emma Smith having been the first. In the summer of 1849, as the Whitings were on the plains bound for Utah, Mary Ann was preparing to give birth to her second child. Tamer Noble was born in late August but lived only until the middle of September.

The Abraham Washburn family arrived with the first group of settlers to Manti in 1849. If not before now, then the Washburns certainly made acquaintance with the Whitings at this time, as they would have worked side by side in the founding of Manti. Mary Ann appears on the 1850 census living in Manti with her parents and her little daughter Elizabeth, but when Mary Adeline Berman dies on 14 Feb 1851, the fourth Noble wife, Susan, assumed the role of mother to the bereft children. Susan, unfortunately, died only three months later (in May). Thus, from May 16, 1851, until June 12, 1853, Mary Ann Washburn was Bishop Noble’s only wife and probably had all of the Noble children under her care and guardianship. Bishop Noble married Millicent London, his fifth wife, on 12 June 1853; Julia Rozetta Thurston, his sixth, 15 January 1856; and Sylvia Loretta Mecham, his seventh, 4 January 1857. Presumably, these women became involved in the supervision of the motherless Noble children.

10 October, 1853, in Salt Lake City, Mary Ann gave birth to Joseph Bates Noble Junior. He later took the name of Joseph Washburn Noble and lived until age sixty-seven, raising a large family. He was the only one of Mary Ann’s five children by Bishop Noble who lived to maturity.

Hyrum Noble was born 11 June, 1855 in Salt Lake City. He lived only four days. Later that year, Mary Elixabeth, [sp?] then age eight, died on 10 December 1855. A son, Alfred, probably born in 1857, also died in infancy. Mary Ann’s heartache and melancholy can thus be attributed to a host of troubles, an unhappy marital arrangement, the loss of several children, and the inherent struggles of pioneer life.

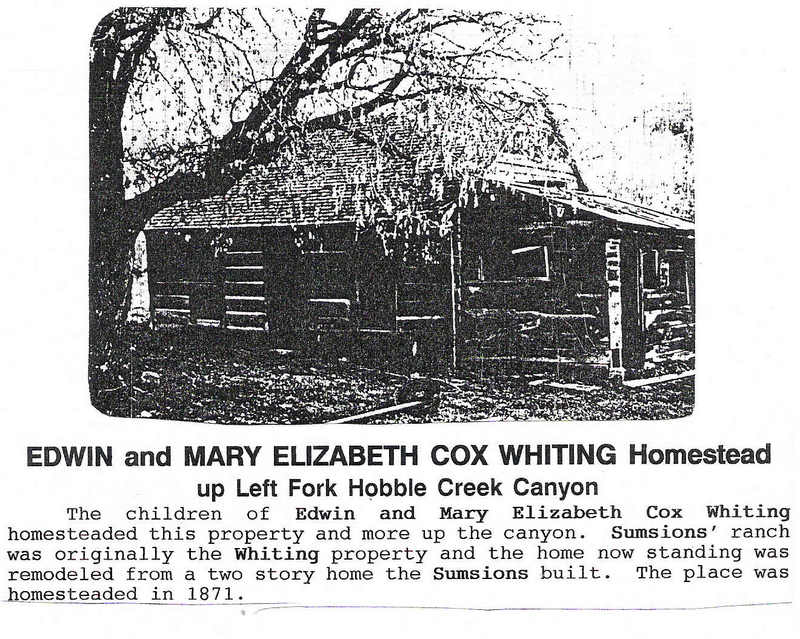

Eventually, Mary Ann went to Manti, and was granted a divorce from Joseph Noble. On 14 April, 1857, Mary Ann was sealed to Edwin Whiting in the endowment house. Edwin was said to have treated her with great tenderness and care. Their first son, Daniel Abraham, was born in 1858. The year 1860 presents us with an important but only vaguely documented episode in Mary Ann’s life. Sometime during that year, a certain Californian named Horace Monroe Frink visited with friends in Manti. Mary Ann told her children and grandchildren about this man, but precisely what she said has not been preserved. What Mary Ann’s relationship with Monroe Frink was (or earlier had been), and why his name carried such an important weight in her mind, is a matter of speculation. We do, however, have at least one hint in this riddle. One of Mary Ann’s granddaughters, Mary Ruperta Whiting Smith, reported that Mary Ann, at one time in her many travels, had “left a sweetheart behind, a sorrow she never got over.” Mary Smith continues, “She seems to have been a very sensitive nature and took her sorrows deeply. She named her youngest son Monroe Frink [Whiting] after him.” Horace Monroe Frink’s namesake, Monroe Frink Whiting, was born two years after the Californian’s visit to Manti. For the thirty-two year old Mary Ann Washburn Whiting, this visit must have triggered memories of earlier events in her life. But precisely when the alleged early romance is supposed to have occurred is a confusing question. Mr. Frink, born in 1831, and Mary Ann, born in 1828, may have associated with each other in Nauvoo as children. Frink, the son of Jefferson Frink and Emily Lathrop, became acquainted with Brigham Young during the Saints’ last days in Nauvoo. “When the original band of pioneers left for Salt Lake Valley, [Monroe], then a lad of fifteen, was chosen as one of the drivers. He did not remain long in Salt Lake Valley but pushed west on horseback, arriving at Hangtown, California in the fall of 1847, and was at Sutters’ Mill when gold was discovered. Mr. Frink returned to Missouri on horseback and immediately outfitted a covered wagon for the return trip to Salt Lake City, bringing with him his maternal grandmother … a sister Sibyl… and two half-brothers. .. .In 1851 they joined the caravan to San Bernardino, California. During his stay in that state he served as guide and scout for General John C. Fremont, and also as scout and dispatch bearer for Commodore Stockton. In 1854 he located in San Bernardino Valley … Mr. Frink became one of the pioneer orange growers of the valley. He died July 28, 1874.” Plausibly, Mary Ann and Monroe were “sweethearts” sometime before the pioneer vanguard company left Winter Quarters in 1847. Yet Frink was only fifteen at this early date. If Mary Ruperta Smith’s report is accurate in the matter of who left who behind, then this romance would have occurred after Frink’s return from California. Yet by this time, Mary Ann was already married and a mother. The particulars of this chapter may never be sorted out. This much we do know, that Monroe Frink’s name is memorialized in more than one place in Utah: on monuments to the vanguard company of 1847, and on every document inscribed with the name “Monroe Frink Whiting.”

In 1870, the Federal Territorial Census of Utah reported that Mary Ann (age 42) was living in a Springville household with her three sons: Joseph B Noble (16), Daniel (12), and Monroe (7). This indicates that Joseph Noble Jr. fell in with the family. In matters of work and play, he was a “Whiting” boy. Edwin appears in the census in a household with his first wife, Elizabeth. But his various families must have been living in close proximity to each other, since the respective households of his four wives are numbered sequentially by the numbers 139, 140, 141, and 142.

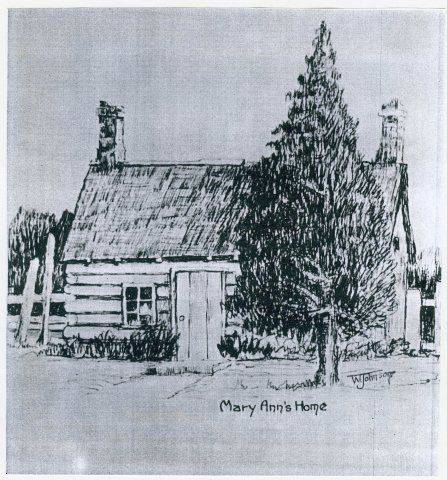

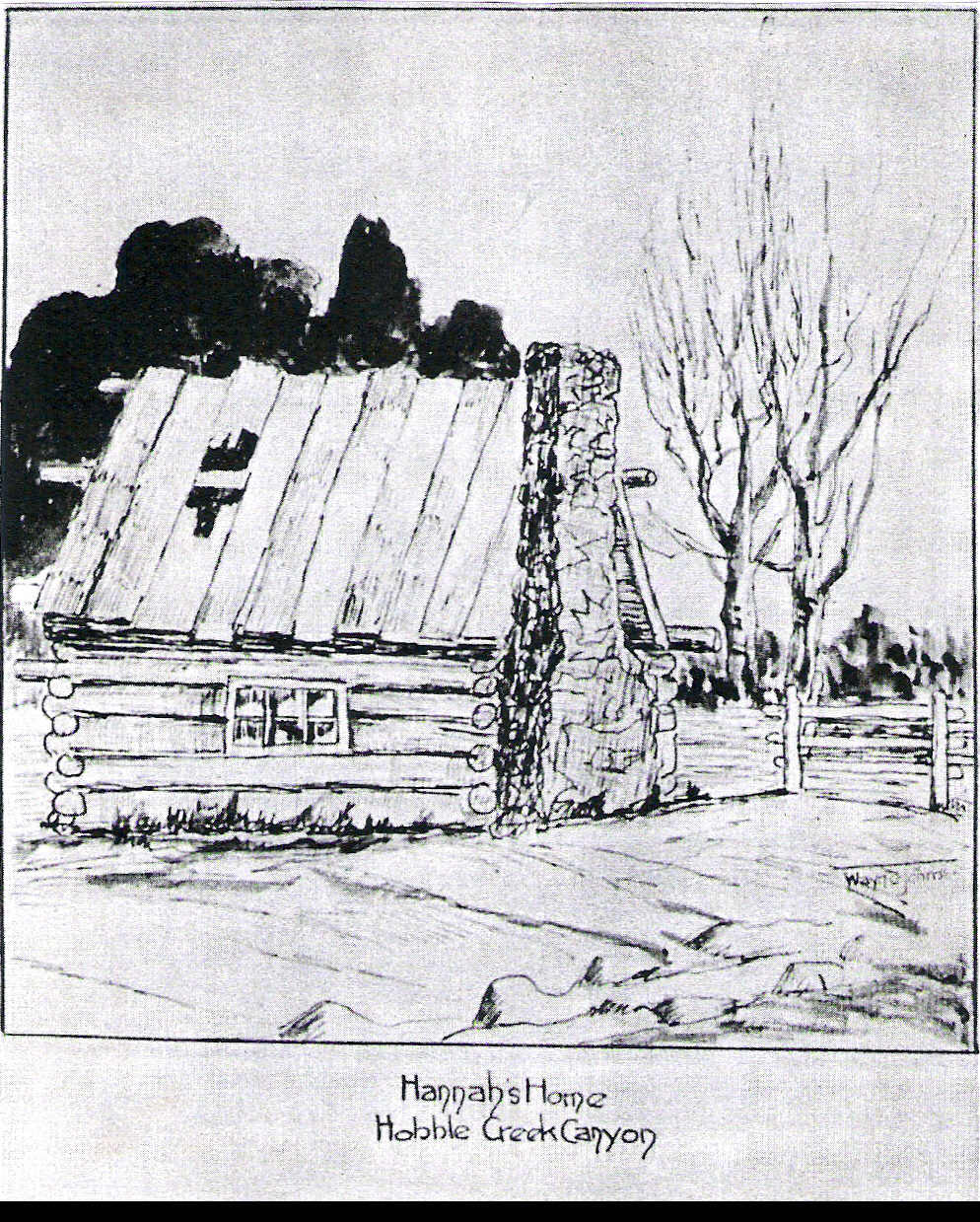

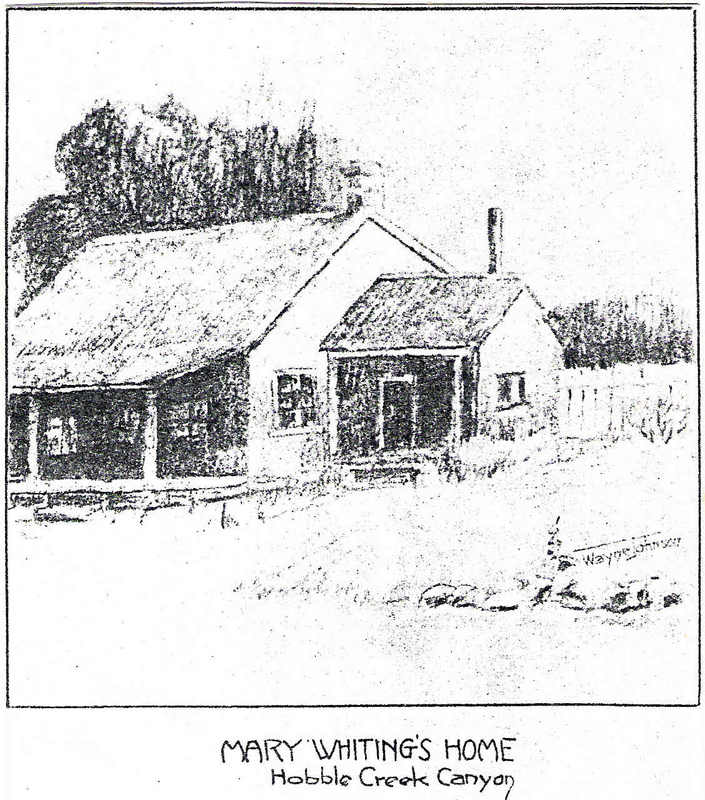

Sketch of Mary Ann’s Log Cabin was located at about 400 South and approximately 225 East in Springville, Utah, drawn by Wayne Johnson, Grandson of Edwin Whiting.

Monroe, who never had a pair of shoes until he was ten, reported later in life that his mother had few luxuries. Mary Ann’s Springville home was a small log cabin located approximately where the art museum now stands.

Having lost so many children, we can only imagine Mary Ann’s concern for the ones who survived. It has been suggested that she was prone to worry a great deal. One grandson, Harold Christopher Whiting wrote, “She was deeply grieved when trouble came as the time when her youngest son, Monroe, left home and went to Arizona to work. It was impossible [for him] to send her word [about his safety]’ She would not be consoled. Before returning home to her, Monroe sent her sixty dollars saved from his wages. When he came back to her safely, she was overjoyed. He soon bought thirty calves and “fattened them for market.” After Daniel Abraham’s marriage in 1880, Mary Ann had to rely more on Monroe for her support.

Harold wrote: “Mary Ann was a fine seamstress and did fine hand sewing. She sewed for many people outside her own family. She was noted for her crochet work and handwork on temple clothing. She was a fine housekeeper and a loving mother, a good friend and neighbor. Mary Ann apparently was never in good health while she lived in Springville. Abby Ann Whiting Bird said of her, “She could not stand rough work that we had to do.” She must have known that she would not live to be an aged woman, and before her death, she made her own temple (burial) clothing. “She said she would make them and have them on hand, and she wished to do them herself so they would be made to suit her. She was very religious about her sewing,” wrote Harold.

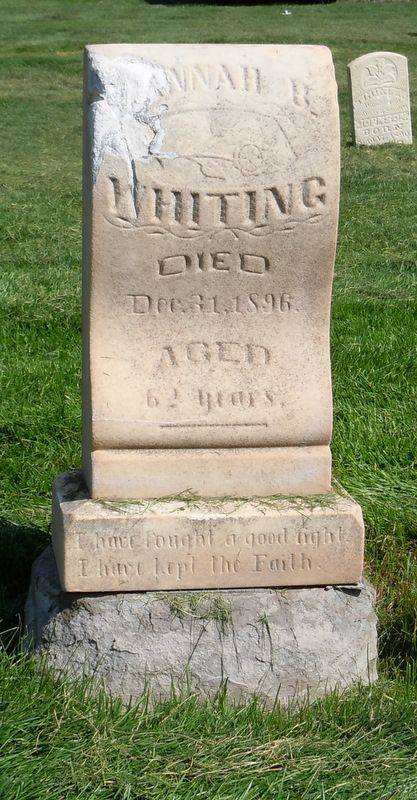

Mary Ann died at an early age, 54, following a stroke, on October 10, 1882 (in Springville).

1 In one version, Pratt said, ‘Be not alarmed. I promise you in the name of the Lord that your wife will soon be a member of this church.’

2 Parley Pratt Washburn and Orson Pratt Washburn were the sons of Abraham’s second wife in plural marriage, Flora Clarinda Gleason.

3 Larsen DUP sketch.

4 Boyack, p. 59.

5 Ibid.

6 Kate Carter, “The Mormons in San Bernardino,” Our Pioneer Heritage, 4:445-46.

.

.

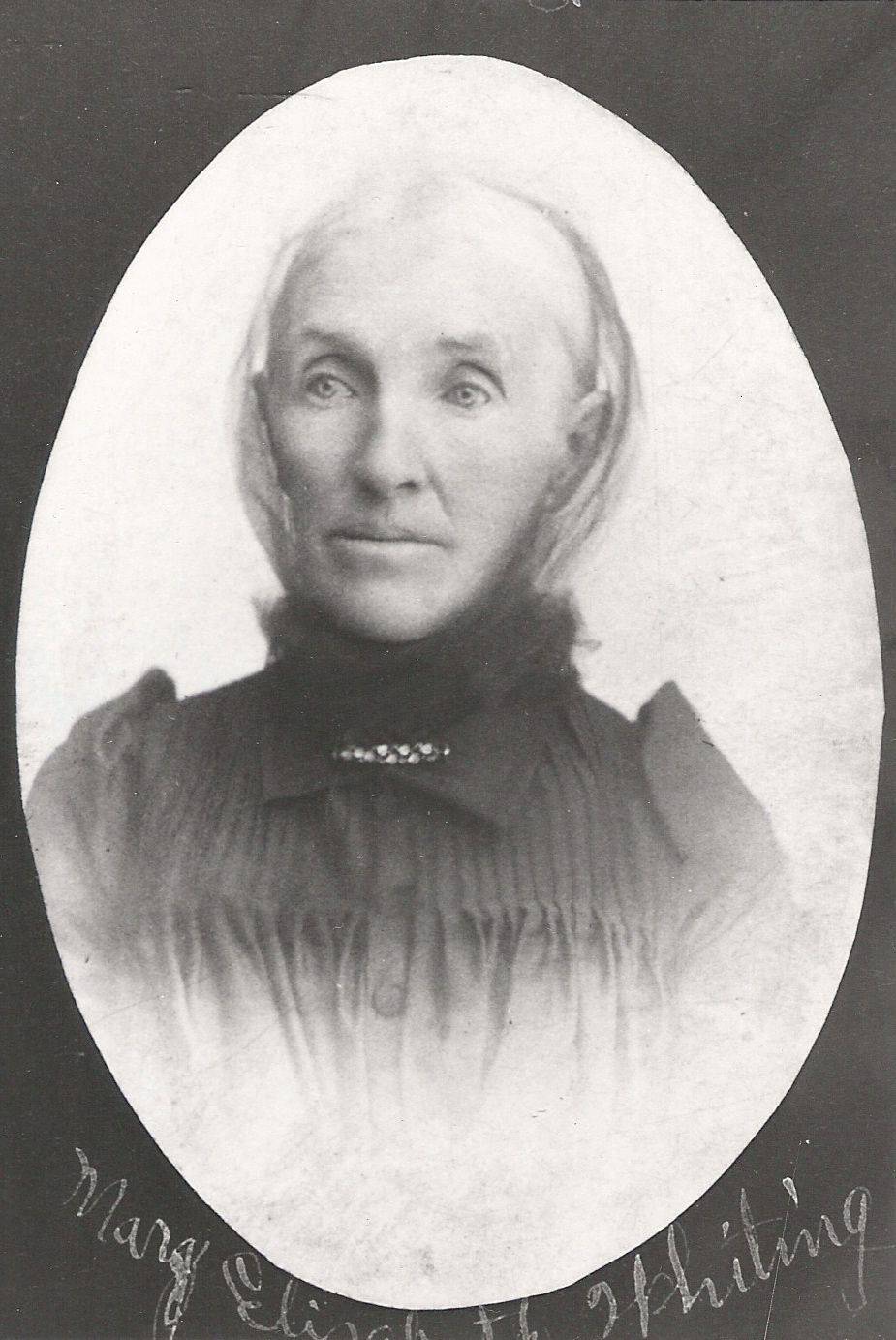

Mary

Mary